00:00 Introduction and Welcome

Glenn Hide: Good afternoon, everyone. Afternoon. Afternoon. We're just waiting for our presentation to be uploaded and we can make a start this afternoon. There we go. Good afternoon. Welcome to what is episode four, which, if this is your first episode, means you've missed three episodes. But the good news is you can catch up on them. So details on how to catch up on previous webinars we'll make available to you.

So to introduce myself, I'm Glen Hyde. I run GMH Planning, a specialist consultancy that focuses on NEC forms of contract, providing training and support to the industry. I'll let David and Ben introduce themselves as we move on.

So this is episode four, which is our third episode associated with compensation events. So the very first episode on compensation events, we looked at the notification and the quotation phase. And then last time out, we looked at assessing compensation events, but part one considered programme because that did warrant a whole session in itself. And now to complete the set, part two, we're going to be talking all about price.

So today's session, that's what we're going to be focusing upon. Now, we'd love you to ask questions along the way. So please feel free to put chat in the chat, ask questions along the way, and then we'll either pick them up during or we'll have a good amount of time at the end to pick up on any other questions as we see fit.

01:42 CECA Introduction

Glenn Hide: So I'd like to introduce you to David from CECA to introduce himself and also a bit about CECA.

David Allen: Thanks, Glenn. Hi again. I'm David Allen, the Executive Director for CECA Southern. Back for part two of the webinar around assessing compensation events. Today we'll be looking, as Glenn said, to address the price element of that.

Some of you who've been on these webinars before will know that CECA Southern are just one part of a member-led trade association that represent organisations delivering and maintaining civil engineering infrastructure across the mainland UK. And you can find out more about what we do by going to our website, and that gives you the whole list of all the bits and pieces we do, which are quite comprehensive.

However, from the training and awareness perspective, we deliver NEC training and we understand that our members can face enormous challenges in getting compensation events approved. So I'm really pleased that that's actually going to be the focus for us today. As I say, to learn a bit more about us, please visit the website and we can sort of update you on that.

I would also echo what Glenn's just said. If you have questions of your own, please put them in the chat function and we'll all learn from them. This is all about collaborating around how we use the contract and some of the challenges we have. And unless you sort of get those across to us, then we're not going to be fully aware.

So with that, I'll hand you back over to Ben from Gather to take you on to the next stage.

03:22 Session Overview

Ben Walker: Thank you, David. Good afternoon all. Yes, I'm Ben from Gather Record Management. And today's episode is, as David and Glen have said, all about assessing compensation events. And this time, we're going to focus on price, having looked at time impacts last month.

So quick overview, quick recap on compensation events. Glen's going to take us through that, and we're going to look at that compensation process just to orientate ourselves and remind ourselves where on that we are. We'll just also recap on the dividing date. We'll look at some examples and the significance of that.

Then we're going to jump into the real sort of main topic, and we've broken this into two parts. First bit's pretty simple. It's how to assess the change to the prices by agreement, using agreement to use a basis of rates or sums as the basis of assessment. And we'll look at why you might do that and actually probably encourage you to do it where the conditions and circumstances make sense.

Then we're going to break into the bit that personally—I don't know about you, Glenn—I find is not well understood. So every training session I've delivered over the years, I try and squeeze in this a little bit of practical theory, do a kind of case study, do a calculation really to tease out whether or not this clause, 63.1, is understood.

And to do that, we'll look at two worked examples. We're going to look at a deletion of an item from the scope and also a change to an item in the scope. And on both of those cases, we'll be using the default approach of defined cost and the resulting fee. So looking forward to that. Should be a good one.

And then as always, we'll round off with common problems and solutions, and we'll take your questions. So with that, I will hand over to Glenn. What's the compensation event, Glenn?

05:16 What is a Compensation Event

Glenn Hide: I was hoping you were going to tell me, Ben. So, compensation event, well, it's an event which, if it occurs through no fault of the contractor, entitles the contractor to change the prices, the completion date and key dates.

Well, as we saw last time out, just because there's a compensation event, we've got to demonstrate the impact it's had on the programme. So you can't just unilaterally move a completion date every time there's a CE. It needs to be on the critical path or on the chain of a critical path leading to a key date.

It's also set pre-contract, as it says there. So when we're tendering as a contractor, you will know what is a compensation event. They've been set. So the list of compensation events are listed within 60.1. And then there's a few others littered throughout the contract.

So I think it's important to say, consider all entitlements to change the prices and the completion date, because it's not just the default that every CE will affect one or the other or both. Occasionally, it could be neither. Sometimes we'll go through the compensation process and realize that there's almost like an add and omit and it kind of neutralizes itself, and they can be zero. So that's our definition, if you like, of what is a compensation event.

63.6 reminds us that the rights of the client and the contractor to change the prices, the completion date, the key dates are their only rights under compensation events. And again, we'll emphasize that as we go through the session.

And where NEC maybe sets itself apart from other forms of contract is the fact that we're going to consider, first of all, the impact on the prices, the completion date, the key dates assessed together, prospectively where possible and without revisiting. So once it's agreed, that's it. It's full and final and we don't go back.

The assessment is going to be based on the impact upon defined cost and the resulting fee, which will preserve the contractor's original tendering position. And I think we'll explain that in a bit more detail or that makes sense more as we go through this afternoon's session.

07:19 The Compensation Event Process

Glenn Hide: So let's take a look at the process, just remind yourself. You can see the red arrow where we are this afternoon. But first of all, we've got the awareness and the notification phases. So 60.1 primarily is where we're going to find what is a compensation. But as we can see there, there's some insurance provisions in 80.1, some in the options specific for B and D, and then some in the second options like X2, changes to the law, for example, it will be picked up. And also there's space in contract data part one now for additional compensations. So there can be some listed there. So that's where they are.

And then the notification phase and the quotation phase are covered there in section 61 and section 62. So that's what we covered on our first webinar when we were talking about compensation, which is actually our episode two. So we talked about either party can notify. So sometimes the project manager, sometimes the contractor will be notifying.

And then we talked about the fact that obviously the quotation process will be the next one. And we're really going into the detail today as to what that quotation will be made up of. So time we've considered in the last episode three, but we are focusing on the quotation assessment here.

Within the assessment, we also talked about project manager assumptions as well. So that was more in episode two. We talked about the project manager can make assessments or assumptions on which the contractor can base the quotation. So for more details on that one, do pick up on our previous webinars.

But today we're focusing on the assessment phase, and naturally we'll be picking up on the conclusion, which is implementation. So that kind of sets the scene as to where we are in our journey.

09:05 Clause 63.1 Introduction

Ben Walker: Indeed. And if you have a copy of this, which, of course, you have on your desk, not in your drawer—

Glenn Hide: I might need a new one, Will. Mine's getting very tatty now.

Ben Walker: If you've got one of these, get it, have it open and we'll kind of read through. Obviously, with slides, we sometimes for space need to abridge the clauses. It's important to read them properly. It takes seconds, half a minute or so to do it. It's well worth capturing the whole thing and following the language of it.

So we're going to look at clause 63.1. Last time was 63.5. We were looking predominantly in the last episode at that time. We're going to hone in now and target in on 63.1. And this, I don't know about you, Glenn, but this is the one in the training where I put the slide up for 63.1. Everybody knows that, we think we know what it means. And then we go on and we do the next slide. And I'd like to loop back around and just check that we've nailed this. And that's the purpose of these case studies that we're about to open up and have a good look at.

10:04 The Dividing Date Recap

Ben Walker: Before we do that, new to NEC4 was a little bit of drafting that just—and we covered this in the last episode as well for time—but it also has just as much importance to assessing price change. And it's a concept called the dividing date.

And it kind of makes clearer the intention of NEC2 and 3 in that we have to have a static point in time which divides the work done from the work not done, such that we can apply cost and time risk allowances for things that have a chance of occurring that are at the contractor's risk.

And, you know, because NEC's prospective in nature in so many things, whether it's forecasting your defined cost in your applications for payment for options C, D and E, or forecasting the effects of compensation events post dividing date, it's important that that date is understood to be static.

Now, this means that even if we end up revisiting a quotation, maybe instructing a revised quotation, and we might go around that loop a couple of times—hopefully not, but certain circumstances might mean we do—that we lock in that date so we don't keep overwriting and resetting this date. We also lock in the accepted programme current at the dividing date as well. So this brings stability to the assessment, and it also aligns much better price and time assessment.

So that's what it's for. It's not a defined term, but it is described in the clauses in a literal sense. And it's simply the bit that separates the actual defined cost for work already done and forecast defined cost for work not done by that dividing date. Gives us that kind of stable platform within which to apply risk.

12:00 Dividing Date Examples

Ben Walker: I say it doesn't reset. What we do need is a little graphic perhaps that gives us an inkling, a quick look up as to what sets it. So how do we know what that dividing date is from compensation event to compensation event? Well, this next slide should help us with that. Glenn?

Glenn Hide: Yeah, so we picked some examples here where sometimes the assessment is potentially retrospective and equally where the assessment is prospective. One of the, I don't know, maybe more surprising ones people find in training is they don't quite realise that if we take the number one on the right-hand side, project manager gives an instruction to change the scope—well, unless the contractor's had an instruction in writing from the project manager to change the scope, they should not have been doing anything before that instruction. So therefore, that one can only be prospective, as in we'll only be looking at forecast defined cost, never actuals, because in theory, you wouldn't have done any work without an instruction.

And if you have, you need to come on to one of our other webinars to learn why you shouldn't be doing things without instruction. But we'll save that for maybe episode seven.

So that is always going to be prospective. Instruction to stop work potentially will be. These will all be more prospective. So on the right-hand side, there'll be times where yes, nothing will have happened before that element has been instructed, and therefore it will be a prospective assessment.

But there are times where there will be elements where it could be retrospective or we've got actual costs already incurred that we will be assessing maybe as part of the compensation. For example, the physical conditions, there might have been some of the works encountered before it was aware it was a compensation, and then the dividing date will be when the compensation was notified. So there could be an element of actuals, an element of forecast in there.

Weather is the one that probably will always be retrospective because you don't know what a one-in-ten-year weather event is till after the calendar month. So broadly that one is highly likely to be retrospective.

But I think that's the first thing you need to think about. So when we're assessing cost for a compensation event, we need to ascertain—and this should be relatively factual—as to when is the dividing date and therefore are we considering actual or forecast, or occasionally is it a balance between the two? Does that capture enough, Ben? Or is there anything else to add there?

Ben Walker: No, I think it does. And that does align us back to those risk allowances that you're allowed to put in and should put in, in your quotations. And also clause 62.2, talking about quotations for compensation events comprising both proposed change to prices and any delay to completion date and key dates. And that all kind of syncs in nicely when we've got this static date.

So I think, Glen, I would still be using the programme. Certainly there should be synergy between your programme and the events and activities around the compensation events so that we can understand how that price has been built up, particularly if it's forecast. And maybe we've got some good records demonstrating some measured miles or some productivity insights that further support those forecast assessments. And then if you've got that, then fine-tuning for risk allowance, you're building confidence in there. So, yeah, they're all good stuff.

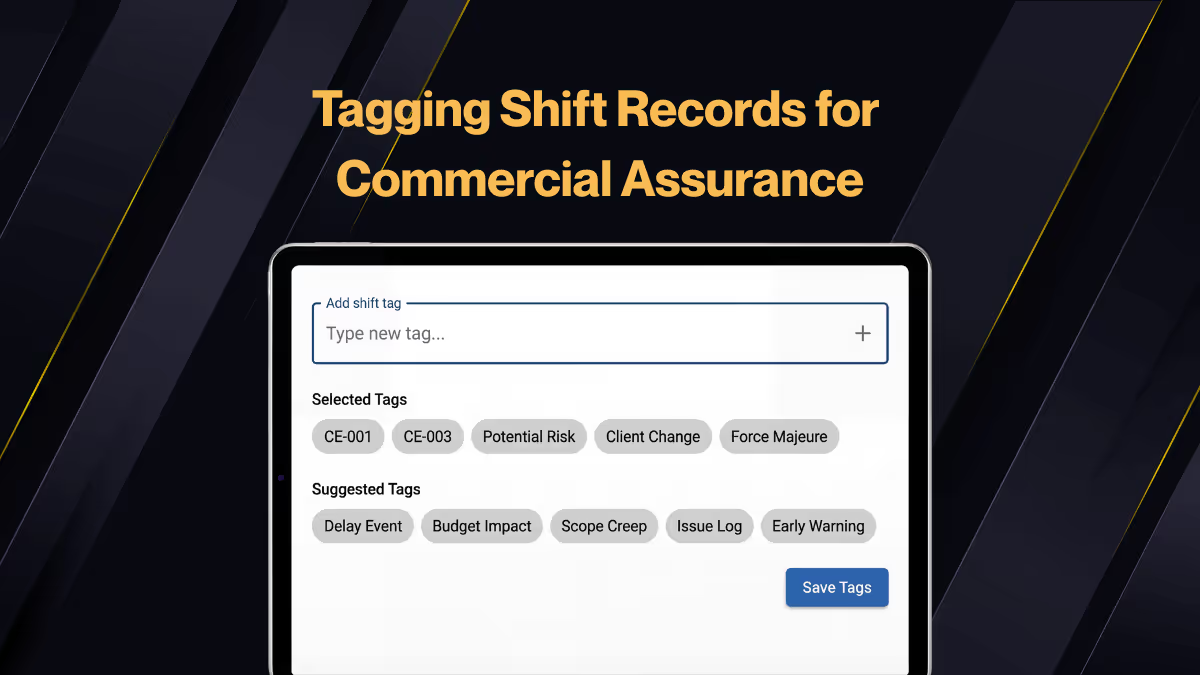

15:28 Clause 63.2: Agreement to Use Rates

Ben Walker: Taking that on board, because this is something we have to do, this dividing date, regardless of the next bit, which is do we base the assessment on some agreed rates and prices as the basis, or do we go into a full-blown defined cost impact analysis? Let's look at those two in turn.

I'm going to start us off with what I think we'd encourage where appropriate, and that is to use clause 63.2. So we leapfrog the clause we're really going to unpick today and we just look at the alternative way of doing it.

I say this isn't the default. There's no default as such in NEC, but this can only happen by agreement. Why wouldn't you agree? Well, you might have some rates or prices that you're making money on, in which case the other party might not agree to doing it. Or you might be losing money. There might be loss leaders, in which case you might not, as a contractor, feel comfortable using those as the basis of assessment.

But let's give a couple of examples. So let's take, for example, a scenario where we have an area of landscaping L01 in the scope. That has a corresponding activity schedule price of £1,100. And we've unfortunately forgotten to include a similar area of landscaping on the other side of the junction. So we need it. So we do an instruction changing the scope under clause 14.3. That triggers a compensation event, 60.1 number one. And we instruct quotations now.

Whilst we're sort of getting ready to receive that quotation—hopefully we workshop that with the contractors so we don't shock and surprise each other and burn management time unnecessarily—it comes to light that, well, this is very similar to a slightly bigger area, a couple more trees in it. Shall we just base it on the price of £1,100 plus a bit? And you negotiate and say, okay, fine, let's agree a price of £1,250 for that bit of work.

That's 63.2 in action. A quantity example might be, look, we want to extend this wall a little bit. Okay, it's not the other end of site. It's not a brand new wall somewhere else. It is a change, not to remeasure. If it was a remeasure because we need more earthworks for some reason or other, then that would just be a remeasure. That might happen even without a change. This isn't that. We haven't had to remeasure this. This is extra wall, but it's only 20 metres. We've just done 2,000 metres squared. We need an extra tiny little bit. Okay, let's use the bill rates.

The scenarios here are where it's a low-value compensation event. And it doesn't make sense to spend pounds achieving the accuracy for pennies, if that makes sense. We don't want to spend £800 fine-tuning that £1,250. Okay, if we did, maybe we get to £1,225 or £1,275. We might be £50 out. It doesn't seem worth going to—so if both parties are in agreement, we can do it.

Again, it might not seem worth building up in the schedule of cost components the people, equipment, plant, materials, subcontractor costs, and then adding a fee on to get to that extra 20 metres squared. You might be accurate to within another £50, £60. Is that really worth it when you consider the quotation might cost you a few hundred at least?

So I think the question here for yourself is ask yourself, are my auditors going to be okay with it? Are my stakeholders going to be okay with it? If they are, have the conversation. And by agreement, you can do that, which I think is sensible. The default position, and that's going to be default probably certainly for the bigger, more material compensation events, is what we're going to unpack next.

Before we do, Glenn, if you want to give us your sort of insights on how this clause works.

19:19 Agreement Must Be Mutual

Glenn Hide: Just on the last slide, Ben, I think, just looking at that word you underlined and made bold, I don't know if NEC need to define that as a term. I mean, you'd like to think they wouldn't need to.

But can I just point out that a project manager saying, "But I want to use the rates" is not agreement. So it's both parties agreeing means just that. So the project manager and the contractor, it says may, may agree. So you do have to come to an agreement to do that. Neither party can insist. Otherwise, we're going to go down the road of where we're going to head for the rest of this webinar.

Ben Walker: Very true. Thank you, Glenn.

20:10 Clause 63.1: The Default Approach

Ben Walker: So 63.1 tells us the change to the prices is assessed as the effect of the compensation upon—and then again, we've got the actual defined cost of work done by the dividing date, the forecast defined cost of work not yet done by the dividing date, and the resulting fee.

The prices are changed by the compensation event under 63.1. The prices are not used to assess the compensation. So it doesn't say the difference between the price and the forecast defined cost. And that subtlety we're going to explore over the next two examples that we're going to run through.

So it's a comparison of two estimates. So the defined cost of the works without the CE and with the CE. And that's what we're going to take a look at. But the easiest way to do that is to look at a specific example, and hopefully these two examples will bring it to life.

Glenn Hide: Yeah, thanks, Ben. And again, just to stress that, the bullet points take us to actual defined cost of the work already done and the forecast defined cost of the work not yet done. And that's important.

But really, the takeaway from this is, as Glenn just said, and I'm just going to repeat it, it doesn't say you compare the price with the forecast defined cost of the work you now want. It doesn't say that. And that's, I think, what lots of us are used to—I did it for a while until I realized I was doing it wrong and put my hand up there. And I'm pretty sure that there's a lot of us out there, practitioners out there, misreading this. And they're taking the price in the schedule and comparing it to the forecast defined cost of the work not yet done that we now want.

And actually, the approach, as Glenn just said, is it's almost a double exercise. We've got to do the defined costs with the compensation event and the defined costs that were going to happen before we had the compensation. And that's what we're compensating.

Remember, to compensate is together to equalise, together to put back where we were, but for the event. So I've got the pleasure of giving you the first example, which is the deletion. And then in a moment, Glen will take us through the change.

22:08 Example 1: Deletion of M&E Plant Building

Ben Walker: So we're going to delete an item from the scope. We're not going to use clause 63.2 here because I think the auditors might have an issue with it, or perhaps the contractor's stakeholder might have an issue with it. Clearly to sort of casually agree, yeah, the building's probably £90,000 might kind of come back to bite us.

So we're going to delete this M&E plant building. For whatever reason, we've decided we don't need it anymore. And we're going to save some cash in the budget and we're going to do away with it.

So the change to the scope is a clause 14.3 instruction from the project manager to delete that building. And you can see that in one picture we've got the building, in the other picture we've got a green field.

Now, probably the case that having the green field isn't free because there's possibly some abortive defined cost already expended. We might have gone and done a survey, we might have gone and put some small road out to it or whatever it might be. So there could already be some defined costs inherent with not building the building, and we must take those into account.

So on the right-hand side of the calculation, we've got the defined cost with the compensation event, and that comes to £10,000. So not building this building is still going to cost us £10,000 for the abortive stuff that we've already done. Maybe we need to restock materials and terminate a small subcontract. It's all going to add up. Of course, it wouldn't be £10,000—it'd be £9,673—but just for easy maths, you'll appreciate we've rounded the figures.

Now what the contract says, 63.1—and this is where you'll be geeky and have this in front of you—is it says the change to the prices is assessed as... So the change to the prices—is to change that £90,000 to a new number—is assessed as the effect of the compensation event upon the defined cost and the resulting fee.

Okay, we know we've got to distinguish between defined cost actually already spent and defined cost forecast, but let's leave that for a second. So we need to look at this impact. It's not the difference between £90,000 and the £10,000, which is where a really good percentage of people still get this wrong. And this is why we've been inspired to create this webinar.

So let me show you what the calculation ought to look like. Here we go. So it's the left-hand bit that we've got to remember to do. And now on an option A contract, this might be the first time that you've got transparency of cost within this part of the works, because we would normally just pay the £90,000 and we wouldn't know the cost effects in the background.

But all compensation events, clause 63.1 is a core clause, and therefore it doesn't matter what the payment mechanism is, what the main option is. We would always have this defined cost transparency. So even in option A, we do our defined cost build-up of the works with the compensation, which we've already said is £10,000. And we do the defined cost build-up of the works before the compensation, without the compensation. And we find that the contractor was actually going to spend £70,000 worth of defined cost in building that M&E plant.

As I say, this might be the first time we've seen it. So the compensation event is the difference between the £70,000 the contractor was going to spend and the £10,000 that they're now going to spend. So the difference is £60,000. And of course, that's a reduction to the prices, and the resulting fee would be—in this example, top right-hand corner, the fee percentage we put at 10%—so that means an overall compensation value of a reduction of £66,000.

Model that back onto the £90,000, we end up with £24,000. Now, this is the tricky bit. If you are trying to explain this to a client, the client may think, oh, I'm going to delete that building. It's a priced contract. I'm going to get £90,000 back. Thank you very much.

And we need to explain that that's not the approach. The £90,000 on the activity schedule, well, the activity schedule is just a fairly crude pricing document. It might have 100 items in it, and it's not separately identifying prelims, overhead, profit. And who knows, the contractor may be making a little bit of money or losing a bit of money on that price. It's really a moot point for the assessment.

What we need to explain to the client is in deleting that building, the contractor is going to spend £60,000 less defined cost, and the fee you put on top of that, you're going to get £66,000 back. And this is why if it's not pressing critical, you might want to explore this with a proposed instruction, a proposed change to the scope, before pressing the button to see what the true saving actually is going to be.

27:33 Scenario 2: Different Cost Base

Ben Walker: So I've put in the top left there scenario one. And let me just bring in a second scenario. This time, if you can see—if you look at the left-hand side of the calculation there, we've got a £90,000 price and a £70,000 defined cost. Let's just look at the second scenario. On this one, we've got a £90,000 price and a £100,000 defined cost.

Forget scenario one for a second. We're now in a situation where we've done the right-hand calculation. All of this would be a single quotation. So within this quotation, we've done this right-hand side with the CE and we come to £10,000. And in this scenario, when we calculate the defined cost of building that building, if we were to do it today, we get £100,000.

So this time it's more than the £90,000 in the price in the activity schedule, which is irrelevant. Again, it's irrelevant. We mustn't fixate on that. The clause does not say compare the price with the new cost. It doesn't say that. It says the price changes as the effect of the compensation event on cost, which means we have to model it with and without the compensation.

And this time we get £100,000. So £100,000 to £10,000, the difference is £90,000. The contractor is going to spend £90,000 less. We model the fee percentage onto that. We get a reduction of £99,000. So on this occasion, the activity schedule price needs updating. There's a couple of ways to do this. We'll touch on that. But effectively, the contractor's going to give back another £9,000 on top of the £90,000.

This is all recorded, so you can watch this again. And you might want to watch it a few times. I certainly had to watch it a few times when it first clicked for me. But it's a very elegant way of isolating the effect of the compensation event as a change, and it leaves the tendered position alone.

So you can see in this scenario—this is not what I'm about to say, take with a pinch of salt, because I've just explained the activity schedule is a crude apportionment of your overall monies against a limited list of activities—but just very crudely, the contractor was always going to lose £10,000 against that price. If you look on the right-hand side column without the building, there's a similar result. So you need to unpick that yourself with a few worked examples to get to the bottom of it. But this theory will hold. We're compensating the effect on defined cost and modeling that back onto the price.

30:09 Fee on Omissions

Ben Walker: Okay, anything to add, Glenn?

Glenn Hide: Yeah, a couple of thoughts. One, we've said, and you've rightly said, that it's defined cost plus fee. Yes, contractors, you do have to give fee back on omissions of work. Sorry, we don't write the rules, but I think if we did write the rules, we would probably say that's fairer than—a lot of contractors seem to think that, hang on, what about a loss of profit? Yep, there's an argument to say that could be unfair, but the contract says it's defined cost plus fee. So with extra works, it's defined cost plus fee. With omissions of works, it's defined cost plus fee. So we just have to accept that, yes, you would need to give the fee back.

That second example I think is really interesting. I do wonder how many contractors will admit it would have cost them £100,000 really, not the £90,000. But like any quotation, the project manager would have to assess if the contractor's assessed it correctly. So in theory, you know, they should build that up to £100K. But like any compensation event quote, the project manager would have to make their own assessment to see if indeed the contractor has assessed it correctly.

And I do find this is the one time that a project manager might say that a contractor has not assessed it high enough when it is a saving rather than obviously an additional element of works.

Ben Walker: Yeah. And, you know, in terms of—I guess you're right about the fee being passed back. I think the thing that contractors, if you can at all possible, just keep clause 16.1 in mind, because if you come up with this idea, if the general pressure is the client needs to save some money and you come up with this as an idea, then I think there's a reasonable route through value engineering clauses where you might actually be part of the solution finding the budget saving.

And actually, whilst your turnover will drop, you might actually better convert half the difference or something like that, depending on what main option you are and what the percentages in contract data say as a bit of profit. So, yeah, maybe turn that into a positive.

Okay, Glenn, I think you're going to take us through this second example, which is a change to the scope.

32:22 Example 2: Change to Concrete Beam

Glenn Hide: Sure. So this time, rather than an omission, we've got a change. So on the left-hand side, we've got a fairly simple concrete beam. And on the right-hand side, we've got a much more complex concrete beam on the top of this structure. So the original activity schedule price was £100,000, which is for this beam. And now we're going to consider the activity schedule price. Okay, what should the change be?

So for this one on the right-hand side, the defined cost with the compensation event will be £150,000. So let's now take a look on the left-hand side and see, well, how do we get to how much this should change by?

So again, similar principle to Ben's one, we're not going to use the activity schedule rate to assess the original basis of the original beam. Because if we now know that that would have cost us as the contractor £120,000—but again, this is obviously any quotation has to be proven, has to be justified, has to be robust. So here, if the original beam would have cost us £120,000, the new beam will cost £150,000. So the difference is now £30,000, not the £50,000.

So again, we're going to apply our 10% fee, which is £3,000. So the change to the price will therefore be a £33,000 increase. How we adjust the activity schedule and similarly with the bill of quantities, we're going to pick up on in one of our bulletins early next year. So that's probably a little bit more detail than we've got time to go through on today's webinar.

But to adjust the prices, there will be a change there of £33,000 because the original cost would have been £120,000 and the new cost is £150,000.

So in a similar vein, we need to ignore the original activity schedule rate and we're building up from first principles to see what the true difference actually is. So that's where it's more.

34:30 Alternative Scenario

Glenn Hide: I think one more example, Ben, where—so this time, if it could have been, if the original structure could have been done for £70,000 and the defined cost for the new one is £90,000, then again, the difference is £20,000, applying our 10% fee. So the change this time will be £22,000.

A lot of people struggle. Certainly on the last example that Ben ran through, just another thing came to my mind where a client deleted £100,000 worth of—well, the activity schedule was £100,000. And they thought by deleting it, they'd get £100,000 back. And when we submitted a quote, there was a fraction of that. And it was good reason why it wasn't going to give them anywhere near the saving they thought it would be.

When they got the quote through, they said, well, that's ridiculous. We get hardly a saving at all. And when they went through it and understood it, they said, well, we're going to instruct you back in then. So they instructed it back in, but unfortunately we'd cancelled all the fabrication and the procurement slots. So to add it back in was now going to be £150,000. And because they'd instructed it, they said, well, we can't afford that. And then they said, well, we'll have to cancel it again. And we said, well, we've incurred costs now because we've already incurred costs.

So it sounded a bit like Laurel and Hardy-ish, but long story short, they had to omit the works and it cost them about £80,000 to not have anything, where if they'd left it alone, they'd have had the works for £100,000.

So I think, Ben, you said there that if there's time, maybe the proposed quotation would be the best route to go down. And I'd certainly echo that where there's time. So if there is, the proposed quotation would allow you to see what this difference will be and then make a decision if you want to go ahead or not.

36:25 No Gamesmanship in Tender Pricing

Ben Walker: Yeah, it's a really good point, Glenn. And again, what this does is to emphasize what you just said, Glenn, is it's isolating the effect of the compensation event on the cost. So it's totally uninterested about what the price is. We just superimpose that change back onto the price to preserve the tendering position.

So when looking and pricing, it's important to know when you're pricing work, right? Because if you suspect that this client, you know, they keep changing their mind, they're going to need—they've said they're going to need one of these. I think they're going to need four of them. There is no benefit to leaning up all your rates and loading that one item in the hope that when you get, if you get three more, you're going to get three times that price. You're not. The extra three will be assessed in defined cost and you'll pay the extra.

So there's no sort of tender pricing sort of gamesmanship. There's no gamesmanship. And we chose these figures very carefully to illustrate an important point. You'll see on this second scenario, the defined cost with the compensation event is £90,000. The defined cost without the compensation is £70,000. And the thing to note there is that the defined cost with the compensation event is still less at £90,000 than the original price.

And you might find clients are reluctant to understand, well, why would I pay—hang on a minute, I've got the full details now. It was only going to cost you £70,000. So I ought to be able to have the thing that costs £90,000. That's still making—you're still making £10,000. That argument is deeply flawed.

No, no, we tendered it in the round. And this part of the works were going to cost us £70,000. And now they're going to cost £90,000. You can't wipe out my tender advantage just because you want a slightly different-shaped beam.

And if we go back to scenario one, I think there's a lot of contractors out there who may well be losing or winning—and not just contractors. You talk about clients as well who may win or lose money unknowingly by approaching this incorrectly. Because certainly, Glenn, I don't know about you, but when I first started with NEC, I would not have looked at this left-hand side. I'd have probably got—when we get to the scenario, I'd probably got that far and I'd have thought compensation event was worth £55,000. You got anything different, Glenn?

Glenn Hide: No, no, I think, yeah, exactly that. And I think something you said earlier, Ben, sort of resonated with me as well where it's trying to put you in the same position you would have been. So you would have made or lost anyway. And after the compensation, it's trying to put you back in that same position that you would have been. And that's what I think people struggle with seeing. They don't quite see that.

Ben Walker: Exactly. Yeah, and here I just thought of the other way I might have done it. If I compare the £100,000 with the £150,000, which is the wrong way to do it—in case you're watching this on playback—then you'd add your fee, you get £55,000, so the new price would be £155,000. That would be wrong. The other wrong way to do it would be to delete the £100,000 and put the £150,000 in plus the fee, which would give you £165,000. That would also be wrong.

The bit that's missing from these quotations—and if you look at something like Managing Reality, that box set there, you can see the suggested template for setting out a quotation has this sort of before the compensation and after the compensation event defined cost assessment, and it's the difference in the two which is what gives us the effect of the event on defined cost. And that's the crucial bit.

40:17 Summary and Key Points

Ben Walker: Anything further to add, Glenn? We are, by all accounts, spot on in terms of time. We might actually have a full 20 minutes of questions, Will, if you want to line us up with some questions. Anything else to add? We've got a few more slides to cover, but anything else on this, Glenn?

Glenn Hide: No, I think we've covered most of the points. And again, I think you said a really good number of things this afternoon, and one of them is that there's no point in playing games with your rates anymore. And that's what NEC has tried to cut through. It's tried to set up good practice project management to avoid gamesmanship, to avoid sort of wrong behaviors.

So if you do have an increased rate or an increased activity schedule rate, well, you're not going to carry on taking the benefit of that going forward because it's going to be assessed based on actual and forecast defined cost. So, yeah, by agreement, if both parties agree it's about right, then we're going to take it forward. And obviously if either party doesn't think it's about right, then okay, you won't take it forward.

The cynical client might say, well, contractor, why are you proposing an activity rate? It must be much cheaper, otherwise why would you be proposing it? And hopefully—but it might be the case occasionally—but genuinely the contract's trying to say, well, look, it feels about right and here's our rough breakdown if you just want a very quick sort of rough calculation that shows it's about right. It's going to save us a lot of work if we both agree this is about right.

So, yeah, we started off by saying you can use it that way, which is good. But then we've obviously gone full circle, which, well, I guess that's your conclusion there, Ben. So wrapping those up.

Ben Walker: Yeah, I think as practitioners, we want to be careful that we're not looking back at too many events and thinking, well, looks like we kind of accidentally did the agreement through the process of submitting a quote, which was based on comparing price with cost. I mean, once these quotes are accepted or assessments being done, they're implemented, right? So the only way to change that then is adjudication.

So I think the best time perhaps to have this knowledge is before you start. The second best time is probably today. So we can move forward perhaps with, if we have been looking at it slightly the wrong approach, this perhaps is that turning point where we can consciously say we're going to use 63.2 because no one's winning or losing lots of money on the tender. The work is similar. It's close by. If you're happy and I'm happy, let's save the cash on putting all that complex quotation stuff together. Otherwise, off we go.

And I guess the overriding thing with this is there's a bit of admin to do. But if we put more effort into the scope, then hopefully there'll be less change. And it was never NEC's expectation to be quite so many variations of balance. And I think Glenn talked about this before. Maybe that's another subject altogether.

43:08 Updating the Prices

Ben Walker: I would just touch on—it's like we've got nearly a dozen questions, so I'll just be brief. I'll just touch on if we are changing the prices by this default mechanism, then we have to do something with that.

Now, we've shown in these previous two examples, there's actually a clause in there, 63.14 for main options A and C, which is to say that the change is in the form of a change to the activity schedule. In 63.15, it states changes in the form of a change to bill of quantities, and that was a little bit more complex.

So we know that there are these different ways of reflecting that implemented price change back into the price schedules. You shouldn't be having a situation where you're paying for the original works off the activity schedule, and then you've got a separate schedule which you're paying compensation events for. Your compensation events should be implemented in the form of a change and update to that activity schedule or an update to the bill of quantities.

And as Glenn said, we'll unpack that a little bit more because you could end up deciding to have a ghost item in the case of a deletion. Here we've got a minus-£66,000 ghost item or a plus-£33,000 ghost item, which I think is nice because it preserves the cash flow. Whereas other options might be to spread that price change over the remaining activities. And of course, there's an argument for updating your activity schedule because it no longer reflects the operations of the programme.

So a few different practical ways of approaching that. Too big a topic to bite now. We'll have a look at that later.

So time and cost risk analysis, of course, included in forecast defined costs of the work not yet done by that dividing date. Just to recap on that. That takes us to common problems, how to avoid them. A couple of minutes on this, Glenn, and then we'll jump into questions.

44:37 Common Problems and How to Avoid Them

Glenn Hide: Yeah, sure. So comparing the tender price with the future defined cost. So issues: incorrect approach, no right to revisit the tender position. And the solution we've gone through today is to base it on the difference in defined cost with and without the compensation. So again, it's playback those two scenarios that we've run through.

It struck me going through today, obviously in the time allowed, another potential webinar is defined cost and how you build it up using the schedule of cost components. So we're talking about the principle; that probably is another worthy webinar that we can go into at another point in time.

Client project manager wants to use actual defined cost late. And that's just a misunderstanding of how to apply the actual and forecast. So understand the dividing date, that is static for each compensation. One of the CECA bulletins we've done recently is ‘Should you be using actual defined cost?’. So we've got a bulletin already, pick up on that fact.

So emphasising what the dividing date is, how it works and how the majority—not always, but a majority—of cases, it will actually be a lot more forecast than people sometimes imagine.

And the waste on resources: complex assessments, quotations are expensive. If it's a low value, it really doesn't seem worth the effort. So find a quick way. Use 63.2, agree the rates or proportional ratios of those rates and see if you can just come to a quick conclusion. How much would it cost to argue over pennies? As Ben said earlier, it really isn't worth it.

Ben, do you want to pick up the other three?

Ben Walker: I will, Glen. I was just looking at the questions, so hopefully I get the right three. You went down, didn't you? I'm odd, you're even.

So defined costs are not clearly built up. So unsubstantiated defined costs, particularly where you're forecasting them, right? We need good records and stick to that short or full schedule of cost components and keep those records. It shouldn't be a guessing game.

And again, a really practical tip with this is: build those up together, right? The timescales in the contract for submitting and accepting quotations are—they're not maximums. They're not targets. And you can completely disregard them if you are working on them together. I say disregard—you can submit and accept on the same day is the point I'm making.

And if you're working efficiently and you've got that co-located way of progressing these things together, then take advantage of it.

Use of fixed prelim or prolongation rate. Yeah, so there's no fixed prelim or prolongation rate. I've been on jobs where we've come up with one and it's been quite practical to use. It's quite a pragmatic approach. So we might establish the different sections of the work, and if those works get delayed, if the sections or the whole works get delayed, we know that translates to certain overheads, certain people, certain equipment, fences, security, that kind of thing.

So I wouldn't say completely rule it out, but you've got to be comfortable with it and maintain those so that you're aware of what they are. And you must still follow the rules. So the proper assessment would do that build-up from first principles across all of these. There's no separate prelim rate.

And narrative around price change, difficult to explain. So client confused, paying for something that has been deleted—"I've still got to pay something even though it's been deleted?" I think we unpicked that there. It's in the message, in the way in which you're talking about it.

You know, the origin of "claim" is to cry out, in Latin. The origin of "compensate" is to work together, to balance, to bring equality. So I think that conversation around putting the contractor financially back in the position they would have been might help that theory come over and build a bit of distance between the prices and, of course, the approach you take to them.

So if we know this upfront, then we can be cautious in talking about budgetary savings and what the omission of something, deletion of something, might do.

49:02 Q&A Session

Ben Walker: Okay, that gives us time for questions. I think there's a little bit of lag on getting the questions on the screen. So here we go. Here's the first question.

So, can the project manager—sorry, Darren, you had two questions, we've jumped on the second one—can the project manager request that a CE is broken down into two separate CEs, one dealing with the cost of change excluding any programme consequences and the second dealing with the programme consequence?

So the answer is no. And actually, it's not desirable. And the whole sort of big nuance with NEC is that we deal with time and money together. So we are—the big payoff there is that we are getting better budget certainty and outcome earlier on in the project. We're dealing with change in small chunks. We've also got the staff dealing with the actual works contributing to that in a contemporaneous manner. We're not sort of wrapping up the admin several months, years afterwards with people who weren't there anymore.

And in a sense, yes, it's a bit more—I would say, yeah, it's a bit more difficult. I wouldn't say it's more difficult. It's a different approach and it's more similar perhaps to the tendering of the works, the whole of the works. We're just doing a smaller chunk of that. So we do need that kind of estimating, forecasting skill set in the team, even on the priced contracts, in order to do this properly.

So no, time and money together. I still see correspondence: "Here are our direct costs; we'll let you know the time effects later." That's not a compliant compensation event. We must deal with time and money together. Anything to add there, Glenn?

Glenn Hide: Yeah, just to echo: time is money, so we can't separate the two. And it always amazes me how people think, "Oh, we haven't got time to look at the programme bit now." Well, how can you not have time? And if it feels difficult to assess the programme element now, I can promise you one thing: it's going to get worse with time, not better.

So people think that if we, "Oh, we'll give it a bit and we'll be able to see what the programme impact is." What information you've got now is the best, the least subjective you're going to have ever. So deal with it, tackle it head on.

Ben Walker: So thanks for that. So the next one's from Zach. If a compensation event was notified and accepted on day nought—so that's the dividing day probably—and the contractor's taken 180 days to price. So maybe they haven't put their quotation in.

I mean, if they take more than three weeks under the contract, the project manager has to assess it. So it's one of the rules under 64.1. If you don't get quotation within the time allowed—because you can extend that within that three-week period. But if that's not happened, then you have an obligation as project manager to assess it yourself.

So NEC is all about keeping the momentum. I think the only way you could get to 180 days is that if you get stuck in that cycle of submitting within three weeks and replying within two weeks, and your reply being "I instruct to revise," you could, in theory, stretch it out to 180 days.

Do they still benefit from using the forecast defined cost? Yes, because certainly under NEC4, this is super clear now. The dividing date is set—in this case, if it was a change to the scope, it would be the date of the instruction changing the scope. That was the obligation at which the contractor has to act on that instruction or at least, you know, take into account the scope has now changed.

And therefore, that will be set in stone, as would be the accepted programme that was current at that time. Although refer to the last episode for seeing how we advanced that programme under clause 63.5.

Anybody anything to add?

Glenn Hide: Well, it says, do they still benefit? Well, or disbenefit, of course. And don't take 180 days to do a quote.

Ben Walker: No, don't do that. And don't forget your obligation to assess it. Have a look at clause 64.1.

Right. We'll probably pick up on this in the next episode, actually. The last bullet point on that is an interesting one—withholding acceptance to a programme for a reason stated in the contract. So finding a reason that the contract not withholding acceptance programme gives you the task of assessing the compensation event as project manager. So just be careful.

53:12 Assessing Quotation Accuracy

Ben Walker: Okay, so Alex has said it can be very difficult to deem if the contractor's quote based on the effect of the defined cost is accurate and then even harder to make an assessment. Do you have any advice on getting a true form of quotation?

Well, I think it's like any contractor's quote. It's really important that the contractor tries to set out to demonstrate that their quote is a reasonable quote. I think we mentioned we'll probably pick up on a separate webinar elements of how you build up the quotation in line with the schedule of cost components. So justify that, you know, the rates you're using, the durations, make it clear the risk you've allowed. So just bring, make it as substantiated as possible what the quotation is and why it is.

Because, look, any project manager is going to be wary of a contractor's quotation because they're thinking they might be trying to take advantage or, you know, take excessive costs. So like anything, I think you've just got to break it down as detailed as you can and substantiate it to make sure that it is based on sensible prices and sensible amount of risk as well. So transparency in the quotes is I guess the biggest advice I can give.

Glenn Hide: Yeah, thanks, Alex. I think records, records, records, right? And we spent a lot of time fine-tuning the Z clauses, right? And loads of lawyer time doing all that. If we look in the scope, use that volume two of the guidance—the user guide—how to write scope, chapter three in volume two, how to write scope. In there it sets out what you should be doing pre-contract.

Not the end of the world if you've not done it yet—you could, because it's in the scope, you can change it. You should be describing how you want your records, how you want your applications for payment to be set out, and that will give you some insight in how defined costs should be structured and presented.

And then workshopping it together. So don't just, you know, get the compensation event instruction for a quote and wait three weeks and the first time the other party's seen it is that, you know, three weeks later. Workshop it together. Narrow the difference. So deal with stuff you can agree on first and narrow the difference.

But I think I've actually drafted a suggested supplement to that guidance note on broader, more broadly, record keeping for the exact question you asked there, Alex. So, yeah, have a look at that as well. It's on LinkedIn.

55:40 Dealing with Repeated Revision Requests

Ben Walker: Okay, Glenn.

Glenn Hide: Yeah, happy to take this one. So how should a contractor deal with a PM who repeatedly requests revised CE quotations and with each submission asks for the quotation to be updated based on the emerging actual facts on site?

Well, it's really strange. They only want to use actuals when it suits them and not when it doesn't. So there's the first thing.

So we're back to the rules on if this is, if the dividing date was in the past, then this will be based on forecast and actuals never come into it. But the more important bit is the repeat of requests for CE quotations. So here's my advice.

First quotation, okay, maybe a contractor might be slightly optimistic on risk or not really stripping things back. So again, justify the quote because we want to try and get it done as quick as possible. But the first quotation might not be agreed. And then there's a second quote and possibly a third one.

But by the time I think you got to a third quotation, a contractor's point of view, you should be absolutely to the bone, in the sense of: that really is it. We can't strip any more out, otherwise we're doing it for a loss. We've put sensible risk and we really believe that to be the final quotation.

So at that point, if a project manager asks for a fourth quotation, my advice is submit a revised quote within 10 minutes. And when they phone you up to say, "Hang on, you've sent the wrong quote, it's the same as the last one," you say, "No, it's not. The top right-hand corner, check that." And in the top right-hand corner is either the date or the revision number. And the contractor's saying, "That's it, that's all we've got."

So if you don't agree with that, we believe we've justified it to the nth degree, in which case, project manager, please feel free, make your own assessment. But be warned, we believe our quote is right. So if you assess it much lower, we might feel the need to look at the dispute process, would be my advice.

Ben Walker: Yeah, I agree. I think the interesting thing with this, without sounding flippant, the bit about the question about wanting to keep resetting the kind of dividing date. I think use a consumer example. Sometimes common sense can be found in the consumer example.

I, for instance, have not even tried to phone up my home insurer and ask for my premium back on the basis my house didn't burn down last year. So I think we've got to see some kind of—the liability on the contractor to price at that date works both ways, and we have to acknowledge that.

But again, yeah, keeping good records and having a programme that's contemporaneous as well. Don't let the programme get so old that the accepted programme current at the time was two months old. We'll try and get that much better.

And also clients should be vigilant, right? If we've got teams going around, you know, three weeks, two weeks, three weeks, two weeks, constantly getting revised quotations. These things are going on forever.

Why are we not identifying the bits of principle or quantum we really can't agree and maybe going to senior representatives in W2.4? So getting the senior representatives involved, because if all we're doing is burning cash and distracting ourselves on today's issues with yesterday's work, that's not, you know—is there a resourcing issue there? Is there a skills issue? So I think I would be looking at that as a client and a contractor, sort of stakeholder in the project: what might need to change there if this is a pattern.

Good stuff.

59:12 Closing Remarks and Next Episode

Ben Walker: Thank you for all those brilliant questions. There are loads more. I think we said, Glenn, we're going to put all these together and write a book or something because there's loads of good questions.

Let me just bring the slides up. I just need to round this off by letting you know about the next episode. Glenn, this is really your bag, I think, isn't it? We'll have to let you introduce this one.

Glenn Hide: Yeah, this webinar is going to be seven hours long. So, yeah, programme—getting it working for you. So we're going to be thinking about all aspects of the programme. And yeah, we'll look at the contractual obligations, but also some practical obligations as well, as to how we can really get the programme, getting the most out of it is the important thing.

So I'm an ex-planner, ex-planning manager. So I kind of recognise that they're important, but not everyone has the same passion or recognition of them. And the important thing is everyone in the project team needs to be feeding in and out of the programme. So the next session is not just for planners. It's for operational, it's for commercial as well.

Ben Walker: Good stuff. And the link to that will be in the chat, if not right now, in the next few seconds. We're going to finish on time for once. David, do you have any closing remarks?

David Allen: Yeah, I mean, obviously there is a question about the programme that will be picked up no doubt next time we speak, but that is key: keeping the programme up together, getting the agreed programme that will help this process, because that's often the first challenge that is faced—trying to identify where a compensation event sits within the overall programme and therefore what the impact really is.

So I think that that's key. And if we could get better at getting that sorted, we'd all be happier. Thank you.

Ben Walker: Thank you, David. Says goodbye from me. One day we'll get that to work properly. Thank you very much, everyone.

Thank you. Cheers.

.webp)