00:00 - Introduction

Good afternoon everyone and welcome to our sixth webinar. Enjoying these, we'll keep producing them for you and we'll pick what we think is relevant topics and if you've got some topics you want to see, do let us know. So a very warm welcome, number six, as we said, and today we're going to be talking about Z clauses and how we should approach them and what purpose they're there to serve and how they can be thought about and maybe better used within our industry. Introduce these guys going to introduce themselves but David Allen from CICA and Ben Walker from Gather, they'll do some introductions along the way so today's topic hopefully you're going to enjoy this session and yeah we're getting into the deep dive of z clauses and how they should be managed and introduced. David, do you want to introduce yourself from CICA?

Thank you, Glenn. Yeah, back again. I'm David Allen, the Executive Director for CICA Southern, and obviously very keen to engage in this episode or this webinar around the option Z additional conditions within the NEC4. Obviously, Ben and Glenn will be best placed to provide an overview around this topic shortly, but first of all, I'll just remind you about CICA, what we do, and its place in the delivery of the UK mainland infrastructure. CICA Southern, the region that I look after, is just one part of a member-led trade association that represent organisations delivering and maintaining civil engineering across the UK. With six English regions, two devolved nations including obviously Scotland and Wales and a policy office in Westminster we're able to engage on industry issues with government and bodies that impact on our industry at both a national and regional level and you can find out more about what we do on our website. However we do deliver training and specifically around the NEC4 contract where again we look to increase awareness and seek to promote fair and equitable use of this tool.

So it may be fitting that we are shining a light on the use of Option Z additional conditions to the NEC4 in today's webinar. All parties do need to understand their duties and obligations under the contract and the inclusion of smart and appropriate options additions will help to support the respective understanding of the parties. However, those additions and amendments that potentially generate ambiguity, particularly given that they are often not tried and tested or equally introduced inappropriate risk distribution, undermine the respective parties' understanding and therefore their confidence in being able to manage those risks. With our supply chains governance procedures becoming an ever greater part in determining their ability to engage with infrastructure client groups, those imposing more favourable T's and C's will find it easier to attract the supply chain that they need to deliver their infrastructure and to get the outcomes that they anticipate. Given the government's proposal to invest over seven hundred and fifty billion as part of its ten year national infrastructure strategy, it is important that the NEC is delivered in a clear and equitable manner. That said, please feel free to add any questions in the chat as we go through the webinar. And I'll now hand you over to Ben at Gather.

02:30 - Why Z Clauses Exist and NEC's Modular Structure

Thank you, Glenn. Thank you, David. Welcome, everybody. And I guess we'll start with the why. So why Z clauses exist. So we'll have a good look at that. And the clue's in the name, really. So option Z, additional conditions of contract, which can, of course, amend things and also be wary of NEC contracts which have already been amended as well, so something else we'll perhaps discuss. You know I like the etymology of these words, so I want to have a look at where amendments come from. It comes from amendum, which is a thirteenth century Middle English term meaning to better, to improve, or to correct. That has some French origins. And even further back than that, amenda, Latin, meaning to free from fault. So there we go. Perhaps that sets the scene a little.

So we'll look at why perhaps we find fault and how to document the fault first. Then we'll look at more general best practice for approaching what some of the NEC colleagues call mischief, and how do we correct that and approach these additional conditions. Then we'll ask ourselves the question, are there three types of Z-clause? It's intriguing, so we'll think about that. We'll look at some Abrahamson principles around risk allocation and the impacts that might have as well on resourcing and how we really weigh up the context of a project before lifting our pen and starting to draft different changes. Glenn will take us through some style crimes, some copy and paste issues and the topic of legalese and how that fits or doesn't fit with our approach. We'll sum up with some conclusions and hopefully point you in the direction of some useful resources and look forward to some questions and answers.

As with all these, I have to say this webinar is not legal advice, I guess particularly this one, none of them are, but hopefully will spark a bit of debate and conversation. And that hopefully adds to the useful dialogue on these sorts of things. And I would say as well, in order to protect the innocent or the guilty, whichever way you like to see it, the various Z clauses that we've dreamt up tonight, we've dreamt them up with the help of AI. So they are not from real contracts, although they might well look familiar.

So before we look at why Z clauses exist, we perhaps just need to remind ourselves of NEC's typical modular structure. And we have these core clauses. We have main option clauses for payment. We have dispute resolution options, secondary option X, which is internationally appropriate and covering twenty nine different options now, which we can pick and choose from to fine-tune our contract experience. Option Y, which are jurisdiction specific and bring us into that jurisdiction law, if you like, the relevance of it. And finally, secondary option Z, which is all about these additional conditions of contract. And a little bit of trivia, if you're drafting a Z clause, and please be careful if you do, you'd start at Z2 because Z1 already exists in the contract.

Now, for those of you who have been on one of my training sessions since 2007, I've always squeezed in this little helpful analogy. I like an analogy. Sometimes the sillier they are, the better and easier we remember the content. So I liken the core clauses to a mobile phone on the basis that if you don't have it you haven't got it, so you need this. This is the foundation of everything that is NEC and the starting point for that optional selection of choices. We then have a flexible approach to choosing a payment mechanism and I liken this a bit to the tariff that you choose based on whether you want the value for money of a contract if you're going to use it or rather budget certainty that a contract arrangement might give you versus the value for money and the pay as you go. So really it's horses for courses and it's down to your context and choice.

My analogy doesn't stretch to dispute resolution, so I'm going to jump that and go straight to these option Xs. And the benefit of these are they're created by the manufacturer, aren't they? We go shopping for Samsung or Apple or whatever brand you use accessories, you know that they're going to work. The only surprise would be if they didn't work and you pick and choose them in combination to get your experience working for you. When we come to Z-clauses, these give us ultimate flexibility. They allow us to take a screwdriver to our iPhone or our Samsung and perhaps ask somebody to make us a case of our own design, perhaps of a specific colour and something ergonomic in our hands. The point here is that we're off into the woods a little bit. These aren't tried and tested. There will be some degree of trepidation about whether or not they're going to work. And therefore, we need to take extra care. And of course, in getting those things made or created or changed, we're going to need a bit of discussion and share our ideas and actually maybe state why the case on the shelf isn't a good fit for us. So I think the overall thing with this is there's no right or wrong, just more or less appropriate, given the context and the appetite for risk resourcing of parties.

06:45 - Best Practice Process for Drafting Additional Conditions

So with that little warm up, I'll hand over to Glenn, who is going to take us through the best practice for drafting additional conditions. Okay, this is probably our most important slide of the night. And there's a lot of context here. So we might have some questions on it as we go through, or we can pick up on the end. So this is best practice. This is kind of our recommendation. There's some industry recommendation as well. I think as an industry, we've got a responsibility to try and police this ourselves. It's very hard for any CD authors of contracts to police Z clauses. Because at the end of the day, no client has to go back through NEC and get sign off from NEC to have permission to change the clause. It's an inevitability that there will be some changes and we're relying on individuals on industry to then make sensible changes rather than just changes for the sake of it or changes an individual wants to make on their own.

Myself and Ben are involved with advising NEC on amended clauses. Ben has in the past, and I've done more recently. And we might propose what we think is an absolute nailer. Oh yeah, NEC want to change this clause. But it goes through such a remit, doesn't it, Ben, of checks. And what we thought was, oh, that's an obvious clause. Then we get it gets tested and hang on. What about this? And that links to that. It's like, oh, crumbs, hadn't thought of that. So NEC, you go through a lot of trial and testing before they will amend any of their clauses. And Z clauses don't go through that same level of scrutiny. And that's where sometimes the problems do come about.

So here's some best practice. Think about why. Why do you need an additional clause or a change to the clause? What's the fault? What's the problem? What is the issue in the contract that's not being achieved that you need it to? What's the context of the project? How does this create this additional issue? What is it about the client supply chain appetite for risk or resources or governance that causes the need? So why do we need it? And the answer is sometimes it will be genuinely yes, you may need it. So then we've got to think about, okay, what are the options? So first of all, if you don't need it, don't do it. If we do need it, well, can this be solved in the scope of the constraint? Is this something that can be put into contract data as an entry, an additional CE or period for apply? Do we really need to change the conditions of the contract? And what would the risk and resource implications be on the pre and post contract teams? Because adding risk to a contractor would generally increase the tender price and increase the flow of communications that are needed.

Flowchart it, so test it yourself. If you're adamant you think a change is needed, then flowchart it. NEC have written flowcharts. Now NEC four, they're available electronically, NEC three, they rebook. And the flowchart's pretty useful, because it takes you through any process within the contract from start to finish, as to how it should work. And they mainly wrote the flowcharts to be honest, originally, because they wanted to make sure those authors that they closed all the loops in the contract that they weren't creating problems that at some point, it kind of stops or hang on, there's no response and the contract doesn't say what happens next. So if you are convinced you need it, then flowchart it through to a conclusion. Does it fit with existing processes? because the amount of times that Ben and I see Z-clause is that then contradicts something that's already in the contract and straight away you're creating an ambiguity and that then causes other problems.

And actually if a Z-clause creates an ambiguity, the ambiguity clause says it goes against the party who created the ambiguity. So there is a danger that Z-clause is created instantly is nullified because it contradicts something else and it should found in favour of the one who didn't create the ambiguity, which would be the contractor's favour. That is, of course, unless they change the ambiguity clause. We'll come to that later. So there might be unintended consequences as a result of this additional Z clause. How would I describe my approach to solving the problem in the why statement? So why do we want it? What other parts of the contract should the user be now aware of? Are there corresponding scope or contract data entries that are needed as a result? So by writing as their clause might mean something else needs to be completed. How does this impact the day to day operation, risk or insurance provisions that may be needed? So what consequences could come about because of this particular clause that's been written?

And in terms of draft, what concepts already exist that we can use. So when you're drafting it, use identified terms that already exist. Don't make up your own phrases. Don't write a phrase that's capitalised to pretend it's defined when it isn't. So use the existing phrases we have, identified terms, use verbs, registers, program. Make sure we're using the right language that we currently have within the contract. Have you followed the general drafting advice in the NEC User Guide, Volume Two? So in the User Guide, Volume Two, there is guidance in terms of how you should be putting these together. Have you followed the guidance written by the NEC? Have I at each stage of this process since checked? So get someone else to check it as well. Internally, try and get someone else to at least check what you've done. You can even chuck it to NEC experts. We're more than happy. We're always very happy to speak to clients who want to run by. Could you just check this from NEC perspective? Are we doing a good thing here? There's any number of experts out here who can help you with your draft documents.

So we've seen an increase, certainly within GMH planning. We've had an increased number of clients recently who've given us their proposed Z clauses and said, look, could you just run through this? Give us a sanity check. What do you think? Good, bad, indifferent. And that's great because they're asking for advice. The trouble is they're the ones who are intuitive and recognising the problems this could cause. The ones that don't think to ask are the ones that may be causing the bigger problems.

Ben, anything to add on that monster slide? It's a good slide, isn't it? But genuinely, this is like the thinking of many years of looking at these things and trying to head off the problems. And the phrase measure twice, cut once comes to mind. And I think what happens is sometimes we bypass all of those steps and jump straight to drafting. And if you don't double check the why, with ultimately the client initially, and then really put that out to the supply chain and see how they feel about it, you're creating almost an unexplained change, which can set all sorts of hairs running. We'll look at a few examples of where the perception might be polar different. I think I'd just say, Glenn, on the flow chart bit, if you've got subcontracts, then just be aware that if you're changing the timings to accommodate different governance, if you're changing the timings, for example, then don't forget to be sympathetic down into the subcontracts as well, across to the subcontracts, as my friend Richard Patterson would say.

So we want to make sure that it works as a system across the project, not just across the contract. The other thing I would suggest is when drafting this, if you haven't got immediate access to experts to check, if you're unfamiliar with NEC, then something I used to put in every examiner report for ICE is use the index. If you haven't got the digital version which you can search guidance on, use the index. Because NEC is one of the strengths is each clause is easy to read and digest. NEC doesn't do cross-referencing to other clauses, so that's a good thing, but you do need to take care that you understand the whole of the picture. So if you're in a defect workflow, look up the word defect, check that you've read all of the clauses that mention the word, and then you've got yourself a bigger picture, check it on the flow chart. So it's just that thing about getting the whole picture.

And again, I really think the big lesson from here is, and it would head off so many problems, is just publish your thinking. So initially, internally, perhaps. So talk to the client. I think we need, this is my why I think we need a change. Can I test that with you? What is your appetite for certainty versus value for money? You know, check these things. We might find that we don't need to progress down through here, which, as Glenn said, is in our drafting experience, certainly the case that we find that some things are solvable in other ways.

15:20 - Three Types of Z Clause

Okay, so I pose this question, are there three types of Z-clauses? Well, the answer is no, not officially. But I don't know about you, Glenn, I've always found it helpful to triage them on this basis. So when I look at a contract data part one for the first time and at the bottom I go to Z-clauses and have a look and see how many there are and hold my breath, I try to calm myself by thinking there are probably three buckets here. I only get really scared if the third bucket is big.

The first bucket I would put them in, I call them boilerplate. And these are a little bit outside of, completely outside of my skill set. So I would go and ask a professional to give me a view on the legal and insurance provisions and what's being tweaked and changed. And I'd probably extend that into if there's Z clauses around termination and insurance and things like that. The kind of boilerplate stuff that I just want someone to have a proper look at. And also, one observation would be, I sometimes wonder, and again I'm not a lawyer so I wouldn't know for sure, whether it's even necessary to start re-quoting large rafts of the law, given it's already law, but I don't know. But it doesn't really worry me, I don't really sleep over it, I just make sure that those are treated in the right way.

Then the second bit for me would be constraints. And largely, these are unnecessary to put in the contract. I can see an argument if you're a highly regulated industry, maybe nuclear, where certain things just cannot happen. And therefore, they'll never be able to happen. So we're just going to lock them in hard. And that prevents the project manager from changing the scope. But it does shut down your flexibility. And Glenn's going to pick up on that on the next slide.

It's the third and final ones that worry me the most. And these are the ones that I would look at most carefully. And these are the ones perhaps where we need the biggest explanation of why. Why are we changing the process? It might be to add a new defined term to make some concept work. It might be to allow us to work within the governance that our industry requires us to follow, some internal governance. And that's all fine. And I think if we're transparent about that and the supply chain understand that and they make allowance for it, maybe we're going to take extra long getting a design submission acceptance back or something like that, then that's fine. I just think we need to be clear about the reasons why so that we can plan for it. If we can plan for it and understand it, then we can price it effectively and off we go.

But there are also examples which break processes, and these are just ill thought out, I'm afraid. There's plenty of examples of them where they're just ill thought out. They're not fully appreciating how NEC fits together as a proposition, and therefore just go around breaking things. And we need to be extremely careful about those. And the way to catch those is to follow the best practice.

18:40 - Constraints: Scope Versus Z Clause

Glenn, you've got an example of the second. We're going to leapfrog the first because I think they're fairly self-explanatory. Glenn, you've got an example of the second where, you know, do you put it in scope or do you put it in the Z clause? And then we've got a few of these third ones that Claude has created for us to discuss. Over to you, Glenn.

OK, so here we've got an example of a constraint. No work shall be carried out between ten p.m. and seven a.m. So fairly common requirement that we might have. So in the scope, project manager instructs extended hours for a critical pour. That would be a compensation for additional cost. And the project adapts as a Z clause. The project manager wants extended hours. Sorry, that's in the conditions, contract deed of variation needed, delay, lawyers, do we proceed at goodwill? So the point we're making here is that you can do changes with Z clauses or things like this, a constraint, if you just put it within the scope, then there's more flexibility to change it. The project manager can give an instruction that changes the scope, but they can't give an instruction that changes a condition of contract.

So it's thinking about how we convey this information. So things like working hours, those just need to be constraints within the scope. And then there's much more fluidity there for the project manager to say as a one-off, we want to be working, we've got permission. Yes, you're out of hours. Yes, that'll be additional cost. So all of that will now be a compensation event, but we can do that nice and quickly. Whereas if you've got a Z clause now somehow constraining hours, you can't do that through an instruction. So try and keep constraints in the scope, unless there's a genuine reason to lock them in and they've got to be in certain environments. I don't know whether you're in a, I don't know, a prison environment or a nuclear. Okay, there might be certain things that you can never do, but most cases we can set them to just be exceptions by the rule, but then we can manage those exceptions through compensation events. Nice and simple.

Absolutely. And just to remind everybody, the definition of scope, I got out my trusty book, which definitely needs repairing now. It's in bits. I need another one. So definition of scope is information which specifies and describes the works. We all know that intuitively, right? Drawings and specifications. Or states any constraints on how the contractor provides the works. And it's that that we're talking about. And the gut feel is to stick them into Z clauses. But don't forget that definition of scope. It's a really helpful thing. So I think exactly as Glenn's just pointed out, if you're working in a prison environment, there's certain things a contractor just cannot do. Then that's never going to change, then absolutely hardwire it into the contract. But as Glenn said, if it's in the scope, we've got a predefined mechanism for unilaterally deciding that we're going to change it, and then a predefined mechanism for valuing and assessing that impact on cost called compensation and process. So it works really well. And yeah, why would you tie your own hands for things like lobby movements or working times or noise levels or whatever else it might be?

21:15 - Transferring Scope Errors to the Contractor

Okay, good stuff. Glenn, I think this one is probably up there with ones that don't fit in our minds, at least with NEC approach. I'll just give you guys a second to read that one. And we'll explain what it's saying. So this one effectively makes the contractor liable for client mistakes made pre-contract. So it's saying that the contractor is deemed to have examined all of the scope documents, so all of those documents specify and describe the works, and satisfied itself as to the completeness, correctness, and sufficiency thereof. And shall have no claim whatsoever arising from any error, omission, ambiguity, inconsistency or inadequacy contained therein. I stress this is not guidance on how to write these. No one takes screenshots of this. This is bad, not good. Or less good, perhaps, is perhaps the more diplomatic way of putting it.

And then what you'll see then is you'll see an extra exception added in 60.1(1). So it will say the following are compensation events. The project manager gives an instruction changing the scope except changes to correct errors that were always there from the beginning pre-contract that you didn't spot or that you're deemed to have spotted. And a slightly softer version of this might be a materiality clause. So you might say, following are compensation events, project manager gives an instruction changing the scope, unless it's an insignificant or immaterial change. And again, we just introduced loads of subjectivity into that. It's just a breeding ground for argument.

I wonder what the message really being communicated here is if we were to sort of translate that. And it probably reads something like, we aren't that confident in the accuracy and completeness of our scope. We want you to take this risk. We understand the prices and fee percentage may increase to cover this. We prefer cost certainty over the compensation mechanism that deals with errors if and when found. So for me, that's almost the mischief statement. It's almost the, as Peter Higgins would call it, the mischief statement, the thing that's broken the problem, the thing we're trying to fix. We're saying the contract's approach to identifying errors and correcting them via the compensation mechanism is not for us. And what we prefer is to sell that risk for some budget certainty, albeit it's going to cost us some extra money.

And of course, what we hope doesn't happen is people gamble. And I think the other thing we have to think about is the asymmetry of time and opportunity to information that the parties respectively had when approaching this. You know, you might think that the clients perhaps had months, maybe longer to put the scope together. Perhaps the contractor's only got a matter of weeks or a month to actually review it. So again, I don't think we're here to say this is right or wrong. We're just pointing out that this one appears to deal with the sale of risk, if you like, in favour of certainty. I wonder if a client was actually made aware fully of this, whether or not they would say, hang on, that's not what we want. We will keep contingency for errors in the scope and we'll only spend it if we need to. We don't want anyone gambling or pricing risk upfront. So again, that's the sort of tension there.

Glenn, I don't know about you, but I've never seen a clause, a procurement strategy that absolutely guarantees a hundred percent certainty of outcome and a hundred percent value for money. I just, I think this is all about choosing an optimum on that scale of the context. It's a balance, isn't it? Yeah, I'm at Parliament today, so I've run a session for Parliament and I'm still in the building now presenting this webinar. And obviously from Parliament as a client, it's really important they have cost certainty on projects, absolutely. But we also then talked about, but at what cost? Because they've also got responsibility to use our taxpayers' money wisely. So there's a balance, as you said, of cost certainty and also value for money. So what cost is it going to be to put all of the risk of contract documents onto the contractor? It's going to be massive. So Parliament don't only want a guaranteed price, they want best value and this is not going to bring best value.

Go ahead David. Just coming in on this Glenn and Ben. This is the sort of clause that really does raise issues within our industry because how do you actually define the risk around that clause? How all that said clause in terms of what it's asking you to do as the contractor, as part of the supply chain. You're going to have to realistically consider that but if you don't have all the details you weren't responsible for developing the design doing the investigation and whatever you don't have time to do that what sort of additions are you going to have to consider against the risk profile or do you actually look at it and think well this is something that we can't really manage when we're looking at our governance when we're looking at the potential that might come out of this then maybe this is not one for us.

And then the client isn't just at risk of paying more for having the work delivered. They might actually lose the supply chain that they need to deliver that infrastructure in the first place. So that is a big challenge for our industry. I have seen this clause in action and it's a difficult one to actually manage and you wouldn't ideally walk into this. Unless, as a contractor, you'd had the opportunity to steer the investigation, the development of the design from early stage. If you really want the contractor to take all the risk on, then let them have the time to fully develop that, manage the design process, the site investigation, risk assessment, et cetera, et cetera, and then you'd get a different outcome. But nine times out of ten, the contract set up, the procurement process will not allow that to happen. So this does cause some challenge within the industry.

A hundred percent. So it increases the tender price, it limits the supply chain, it increases distrust between the parties potentially, because now a contractor is worried about the liability and how suspicious they are, because no client's going to write that if they're confident in their documents. So they are potentially wary that there might be some inaccuracies and it's asking for the contractor to price the risk. In theory, nothing wrong with this. A client has the choice to do this, but it's questionable as to whether it gives the best optimum value, cost certainty. And we're trying to balance all of these things, aren't we, as an industry?

Yeah, I don't think our intention tonight is to preach one way or the other or to say something is good or bad. I think probably easier to say it's more or less optimum given the context and the client's appetite for risk. You know, that's really what we're talking about. But also, of course, the supply chain's appetite for risk. If we're putting something out there, I had a good conversation with David earlier this morning, and we're putting something out there that is, you know, untenderable, then we're going to get maybe not the full range of bidders and value that we might otherwise unlock. So I think it's worth just testing the why before we commit to a clause like this and any variant of it, and really scrutinise why we think this is the right approach.

And of course then we see other flavours of this, orders of precedence being written in and all sorts of other things. Why not say why we think an order of precedent might work better than the contra proferentem basis? I used some Latin there, didn't I? The contract's approach which is based on this sort of concept which favours the party that didn't create the problem. You know, why do we think that's better than the other? And have the conversation, at least to your point, Glenn, about trust. That's in the open. We're putting our cards on the table and everyone can understand that reasoning behind it. Why gives you energy, doesn't it? It answers so many questions if we know why something's happened. One of the questions I'd throw in there as well is, why don't you actually talk to the supply chain and find out what they would think if you introduced a clause like this? Get that real-time feedback to better inform any decisions that you then go on to make. Absolutely.

28:10 - Reducing Time Bar Periods

Okay, Glenn, I think you're going to talk us through this one. Sure. So here is a fairly common, not fairly common, an amendment we see, not infrequently. So delete 61.1, amend 61.3. So here, if the contractor doesn't notify a compensation within and normally it's eight weeks, but it's now been reduced down to four weeks, the prices and the dates are not changed. And then it normally says unless the project manager should have notified but didn't. So what this very subtly is now doing is first of all, reducing the timescale that the contractor's got to notify a CE from eight weeks down to four weeks.

Now it's interesting if you go back as far as NEC2, NEC used to say two weeks here and it was the legal fraternity that said to NEC two weeks is not legally enforceable. It won't stand up in court if it ends up there. So after lots of toing and froing from NEC2 to the publication of NEC3, NEC took advice of the legal industry to say eight weeks is enforceable, two weeks wasn't.

Now, in truth, somewhere between two and eight may be enforceable, but NEC erred on the side of caution to say eight weeks definitely would. So this particular client thinks they know better and is saying four weeks is legally enforceable. They might be right, but they'll have to go to court to find out. Certainly NEC didn't take that stance and they went safe with eight weeks. So first of all, we've reduced the timescale by half. So that may or may not be enforceable if it did end up in court.

And now all compensation events are the responsibility to be notified by the contractor. So normally the ones the project manager should notify, the contractor's not time barred on those ones, but they're now time barred on all the CEs, the ones the project managers are obliged to notify as well. That's going to add admin problems, cash flow implications for A and B. And also, what if it's a negative compensation? If the contractor is obliged to notify and it's a saving and the project manager can't notify anymore and the contractor doesn't notify, well, then the client doesn't get the saving. So what was trying to solve a problem from a client's perspective has caused another problem and created a lot more admin, a lot more issues that are going to happen on that project.

So again, fully understand how the clauses interact. If you change core processes, you need to explain why and model out those consequences to make sure you're not causing other problems. You solve one alleged problem and create two or three problems that you didn't know you just created. Glenn, on this one as well, in addition to the example that you're giving here where the time has been reduced from eight to four weeks, we're actually seeing the opportunity or the time for the project manager to respond is often extended. So you are getting the worst of both circumstances here, which doesn't help. And in the long run, if that is something that is embedded in the contract going forward, then you're going to have to build up the resource to actually manage this process. So you're not actually reducing costs from the teams. You're actually increasing the risk profile on the contractor and actually delivering the workload because the risk of actually missing something that is significant grows and that will have to be considered when they're actually looking at procuring the work as to whether this is an environment that we actually want to be delivering in.

I think you hit a great point there David and it goes back to something we've covered before on previous episodes which is about the empowerment and authority of the project manager. If clients are appointing project managers and then tying their hands, that's problematic and I struggle to see why we need more than the one week under clause to make that decision because it is an objective decision. And there's nowhere in that decision where I understand people need to go to boards for acceptances, but this isn't really an acceptance. It is an acknowledgment that a compensation event has occurred. So it's not like we can say, oh, hang on, I'll check with the board. Oh, I've heard from the board now two weeks, three weeks later. Unfortunately, I can't accept this as a compensation event. We can't afford it. That ship sailed. There's either a physical condition, or there's a weather event, or there's an access issue, or there isn't. So really, it's a very objective test. Did it happen or not?

And I think we encourage people in our training, Glenn, to try and give that one-week reply. Try and give that the same day if you can, because why would you hold that process up, particularly for a contractor who's operating on option A or B, where that compensation event implementation, that commercial process to finalise the price change, that's the only way they're going to get paid for that extra bit of work because it's that change to prices that gets included in the next assessment. And so really a project manager acting to promote spirit, mutual trust and cooperation is one that is trying to do that rapidly. And again, I think we said it many times, these timescales are not targets, right? They're maximums. So let's see if we can beat them.

33:45 - Deleting Compensation Events for Late Replies

So this is another one, and again, not right or wrong. Incidentally, on that last one, I think I'll just add that you can see the plausible thinking behind this. We want all CEs notified promptly. So it's not necessarily from a bad place. It's just, we need to understand why, because there might be better approaches. And sometimes I've seen really big organisations through my work in the contract management system world when they actually presented with the data those big organisations revisit that governance and say well actually we've now got empirical data that shows that because we've turned the governance up here it's costing us money here and they're much better to find an optimum. And it's an interesting piece of work, Glenn, perhaps we could explore that in the future, how big data helps us make better empowerment decisions of project managers and governance overall. The other thing I used to find was that the more people in a chain of sign-off for something, the quality can sometimes drop because everyone's thinking everyone else is looking at it. So there's a lot of human behaviour back in all this stuff.

This one's a brief one to explain. The client here wants to delete certain things around the project manager or the client, getting back with communications on time, withholding acceptances for reasons not in the contract, not doing things by the date they said they would do. And again, this might come from a kind of genuine place of uncertainty. So let's play that out. We're saying, look, we have a complex project with strict governance, and we need more time and flexibility to administer it how we see fit. There may well be occasions where we're not going to be able to provide something for the date shown on the program for providing it. OK, so it's a strategy. And without saying it's good or bad, it's a strategy. Again, what we're saying is we don't want to constantly have to administer compensation events and constantly be charged in our mind more money when these things happen.

The reality, though, is bidders will interpret this as a client and a project manager who are likely to be very difficult to work for. They're going to change their mind without warning or thought for our operations. And we'll need to allow significant disruption in our program and pricing. It might not be worth bidding. A perhaps more optimum approach to this would be to elongate some of those period for replies to maybe Z clause some of those reply periods and other things so that the governance is more sympathetic. The contractor can plan up to that level pre-contract so they can allow for it. You'll pay a bit more money but okay it's closer to reality. And then just allow the compensation mechanism to kick in. That will give you that balance of degree of certainty, but a degree of value for money where you're only paying for these things if you fail to provide something or if you fail to reply on time. And, you know, give early warning as well. Dear contractor, I notify early warning that I might be late replying to this design submission. My reasons for this. Let's chat about it. So I think we don't have to see this as adversarial. But at the same time, there might be an optimum way of doing it rather than just deleting the clause entirely. Anything to add?

No, spot on. It's always about what cost is this going to come, so at what cost are we what are we going to achieve. And as you said, contractors are now wary, they're going to allow more program time that increases cost. So yeah, that's not potentially the best solution to that problem. So keep these in and occasionally there might be a compensation but there's other ways of managing, better ways to deal with this than to delete them and then elongate the process, which is a big risk for the contractor. Yeah, if we know our governance is complicated, then price for it or tone it down and then draw on that contingency as and when you need it. The alternative that this appears to do is to try and chuck that contingency at a certainty in advance, which can't be good value for money, can it? But anyway, we could debate. It goes back to the argument, though, about having that collaborative engagement at the right time and the behaviours around the contract and actually addressing the issues that arise. So if you've got a contract, you know where some of the complications might arise. If you're actually engaging with that during the procurement process and engaging with the parties that are all taking part in that procurement, at least you are communicating the intent, you're providing clarity, and people can look at it in a more objective way. Quite.

36:20 - Deleting Mutual Trust and Cooperation

And talking of behaviours, this next one's an interesting one. Glenn? I mean, where do we start on this one? Shall we just leave it at that, shall we? So delete ten point two, the obligation to act in a spirit of mutual trust and cooperation. I mean, look, on training, we talk about ten point one, the obligation to act as stated in the contract and the very useful addition of ten point two, almost creating like an obligation, a culture as to how we should be, which is to act in this spirit of mutual trust and cooperation. Now, whilst I think it is important, ten point one is even more important to follow the rules of the contract. Whatever you think of this, to actually say you're going to take it out, then what message does that bring that you're intending not to act in the spirit of mutual trust and cooperation? We've written a secret bulletin on this. I think it's number fourteen from memory, what it does mean to act in the spirit of trust and cooperation and what it doesn't. But certainly don't take it out. It's a nice reminder. And that's it really, but to delete it gives the very wrong message. Agreed.

37:50 - Abrahamson Principles for Risk Allocation

OK, this next slide, and I think it's the last but one, is just looking at risk, resourcing, and context. And some Abrahamson principles can help here. So there's five things, really. A risk should be allocated to a party if they have the most direct control, they can transfer economic risk, they stand to gain the most, placing it there aids planning and operations, or the loss falls there naturally. So you've kind of got this stand to gain the most or the loss falls there naturally is kind of like the first order of who's dealing with it and where it naturally sits. And then you've got control economic, sorry, control and efficiency, which are kind of related there, I guess, and whether or not it can be insured. So I think that's a useful lens to look through, a useful way of dimensioning the efficiency the matter and whether or not which party should carry it.

Now, again, this is, you know, I would suggest some well thought out thinking by Max Abrahamson. So something that perhaps we might want to have a look at. I think what this translates to then before drafting a Z clause, so having gone through or about to go through that second slide that Glenn talked us through right at the start, so the process for developing to the point where you've got a Z clause, this is perhaps some of the thinking that we do in the background. So what is the context? Size, complexity, sector, ground conditions, and has this thing been done before? What are the client's goals? In particular, a question that seems to keep cropping up with this is what's the client's risk appetite, financial risk appetite? But let's not just assume that means budget certainty. Let's think about that dynamic, that tension between certainty and value for money. What insurances are typical and available? What resources do I have pre-contract to actually maybe improve the scope if we think it needs a further review, maybe do some more ground investigations?

And what resources have I got post-contract who might actually have to, you know, if we ask for a thousand more things that are crucial to the operation of this new Z clause, then someone's got to check those thousand things or fail against doing so. So, you know, what are the implications on our post-contract management resources as well? And then to David's point, I think he said it twice, what's the market telling you? Have we asked? Have we gone out and said, I'm thinking of doing this? What does everyone think? Is everyone still interested? Have a two-way conversation and find out what the market thinks, because this ultimately should be a collaboration. We want to work together towards a common goal. Some want to be paid appropriately. So let's work together on it. And is it fair? Would I sign this if the positions were reversed? What might I object to or put a comment against? And that putting yourself in the other party's shoes, of course, is not just empathy. It's commercially sensible, I would suggest, because it helps you understand the dynamics of it.

And I think this final point, Mr. Abrahamson would say, a perverse combination in the construction industry of a few words breathed out about risk in time to save loss, but a gale of words when it's too late. And this reminded me very much of the late Dr. Martin Barnes's quote about project management is about influencing what hasn't happened. Everything else is admin. And you know, pre-contract we can influence what hasn't happened by setting it up appropriately and I think that's perhaps something else to mull on. Anything else guys? Yeah, just on that, the last two points I think they're probably the most important points, in green, about before drafting the Z clause. The bottom one in particular, it says this is fair. And really, I mean, we're looking for clarity. If people have surety of what's being asked for, what the objectives are, then it makes it easier to actually assess the risk. If it is deemed to be unfair, then that doesn't help. That sort of probably develops the wrong behaviours, as it were, around it. But if it was reversed, what allowance would those drafting or about to draft it actually put in there? How long would that piece of string be? And that really would make you think twice about some of the clauses that are being put in. Absolutely.

42:00 - Style Crimes

Okay, Glenn, over to you on a few style crimes. Yeah, just a few final thoughts really just to pick up. You know, remember NEC is written in straightforward plain language. It's written in present tense, active voice, fewest words and syllables possible. So they've kept the word count down. No more than forty words, ideally no more than twenty words. We're trying to make sure that these are readable, they're understandable. So just think about how you're writing. Just looking at the red there. We won't even justify reading that one out. So look at what you're trying to achieve. Generally avoid Latin. I did a year of Latin when I was at school, but I've forgotten all of it. So NEC is trying to be a stimulus to good management. Another key virtue is clarity. So let's make sure that people reading it can understand the written words and we don't add in mutatis mutandis and inter alia for example, even force majeures. So we need to try and avoid those things, which you'll have to Google and look up, see what it says.

Avoid copy and pasting as well. So don't just copy and paste stuff from one into another because inherently that causes problems. You bring in something that was relevant to another project that's not relevant in this one. So it is a kind of false economy. If you are going to do it, then obviously just check what you've brought in and then rewrite it. But don't just copy and paste because we see this so often that some limits are brought in that are just, they even refer to another project altogether or something like that, which is clearly complete nonsense. And again, creating ambiguities by trying to allegedly save self time. It's a real dangerous time to be lazy, though, isn't it? Effectively, you're leapfrogging all of this. By copying and pasting, you're leapfrogging everything there. And it's just very dangerous practice.

Yeah, another sort of point really relating to the copy and paste and also to the words that you sort of spoke about at the beginning when you were defining what the amendment actually meant, you broke that down. We have had instances of contracts being let under a framework where the conditions have had to be amended in the end for the particular supply chain to be engaged because the T's and C's didn't quite actually match up and then a repeat contract would then go out for procurement and that original document would then be used as the template with the changes still in there and so you're then carrying forward something that was project specific into the next contract and the next contract and actually making it worse because the intent was there for a good reason but then it's kept being replicated across to contracts that are set up and procured that are intended to be different and have different setups but those Z clauses have still been carried in. And we have had that, so that is a major concern. Fair enough. You've got your template for this contract that's done. Separate it, okay, and see what really needed to happen in that contract and reflect on that as to whether you still want to keep it for the next time. But certainly, a lot of the project specific ones should fall out.

45:30 - Conclusions and Useful Resources

Okay, so a few conclusions and then a few useful resources. In fairness, we've repeated some of these. And these don't feel like the same conclusions as other webinars because they're more about a process, aren't they? A technical process. So remember why, think about the why, and share that reasoning. If you're going to change a contract, the reason why you want to change it should be communicated, ideally pre-tender. We want to respect the supply chain, and we want to get best value, and there's a balance there to do it. Don't buy certainty unless it's cost effective. Manage the tension between certainty and value for money. And of course, follow that best practice and you're less likely to go wrong. Share the thinking. Share the thinking.

David Allen, any parting thoughts? Just really follow the principles and engage with the supply chain that is going to help support you and deliver the infrastructure because ultimately you won't be able to do it on your own and the supply chain in itself is an important part of delivering that outcome and ultimately working together collaboratively is the way to deliver outcomes that work and are the best value.

Super. And Glenn, I'll just mention next webinar soon, we're doing March actually. And one more thing that might turn up over the next few months is watch this space if you're following Gather on anything. We're looking at a few awards, some awards for good practice in the drafting of contracts. So potentially one to look forward to.

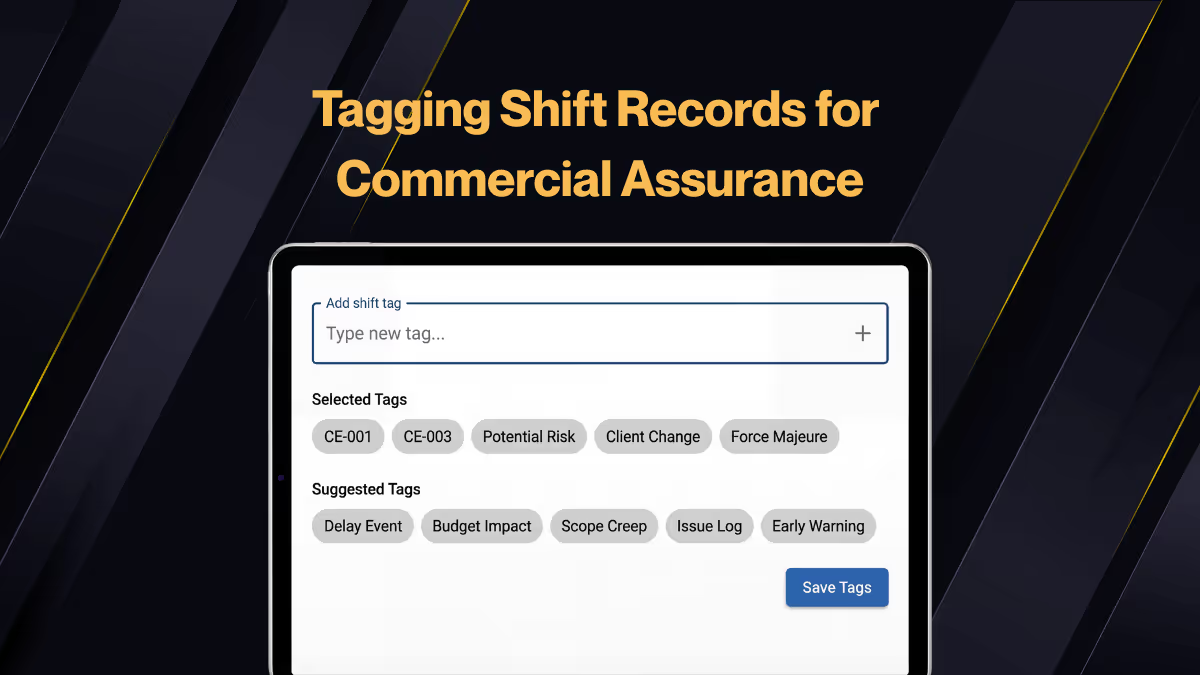

And some resources here. So do connect with us on LinkedIn and we publish lots of stuff on there. If any of this has been of interest there's a few links there to useful stuff. And I think on the matter of Z clauses there's two useful publications that are up at the top. The Infrastructure Scotland guidance on the use of additional conditions of contract, so this is the official guidance produced by Infrastructure Scotland. And one of the organisations within Infrastructure Scotland, the Rail Delivery Group, has got their own guidance on this, of course, which talks about Z-clauses within the railway context. And also, our esteemed chum, colleague, Robert Geddie, has done some great work at Infrastructure UK on their Z-clause supplement, which has looked at some specific Z-clauses that might be needed and has got some good language that could be used. So I would encourage you to look for those three resources. The links are on the screen. And there's a few other resources where you can learn more. And we look forward to questions. Glenn, anything to add? No, just thanks for your time. And send me questions. We'll get through them now.

47:00 - Q&A

Thank you. OK. If you're the one person who's put a question in, we've got one in the chat. Whoever that's from, there's a few. OK, go on. So I'll go. How enforceable is a reduction in time bar periods? So as Glenn stated, there's some doubt as to whether a few weeks could be defended, but eight weeks is probably OK. I think it's probably even in the law of the land as to whether or not the time period that you've given is reasonable. So a time limit clause would be valid if the contractor has been given reasonable opportunity. So it's all about the opportunity, not the time. Practically, can you complete the task or action that's needed? And as long as the opportunity to do so is there, you're probably on safer ground. So I don't know if it's about whether or not it will stand up in court. I don't have a crystal ball to see that, but I'd certainly be thinking about it. Eight weeks feels right. We've got a good provenance to say it's been tested. Clearly the contract allows us to change it. So it's probably somewhere in between eight and two, really. But again, I ask the question, is the benefit of even moving it worth that effort and risk? And I'm not sure it is, personally, but anyway, it's a choice.

Glenn, you had a different one on your screen, or do you want me to pick up some more? Yeah. Can you add things into the contract, i.e., if you fail to get a question answered, you can approach site agent who has the opportunity to decide if reasonable? What does it mean by reasonable? There's already a provision for that, isn't there? If the contractor wants to accelerate, so the contractor wants to get the work done quicker than the completion date, then they can approach the project manager, put a proposal together, and the project manager can accept that instruction or accept that request. I don't think the scope should be a negotiation. I'd probably push back on that one. If you look at the reasons for withholding acceptance of a design submission. One of those reasons is more information is needed. So there's clearly a dialogue pre-acceptance that the project manager can ask for more information. So I think that works. And the project manager can change the scope where an instruction changes the scope. And the project manager can change the scope in the absence of a proposal, but I mean that's essentially a unilateral decision, isn't it? So if the contractor has a reasonable proposal or a reasonable idea and they put it forward for acceptance, a project manager either has to accept it or has to withhold acceptance for one of the stated reasons and explain what they are. And then there's a dialogue there. So I think that mechanism's in but I think it's important to keep it kind of in the hands of decision making rather than the scope being a negotiation.

There's a question from Colin, I think, Glenn. He came back on the first one. So a genuine question, I think, for a regional local authority that may only have a PM they have appointed that has limited experience and often sits with multiple projects to deal with. Having more time to actually review something is helpful, so their extension for reviewing time is helpful. Yeah, I was just going to come back on that. These Z clauses tend to exist to the negative of the other party. And I totally understand that scenario where the project manager is stretched. But to then put more risk and cost onto the contractor to balance that out isn't the best approach. Resourcing the project properly from the PM's team, providing more time in their day, or if they genuinely can't make a decision within a week, keep that one week, but perhaps raise an early warning and let the contractor notify that. Something wasn't done on time, but have that dialogue and keep everything transparent. You can still work with those constraints and decide not to change it just because you're stretched, because you're just passing the problem on to the contractor to price. Yes, agreed.

I'll take these two. On the first one, is there a difference between a Z clause and a W? I don't think there is. I think they've both got the same purpose. I think that Ws are dispute resolution option clauses. I think that's the historical basis of them. But when they're an additional clause, they're the same, I think. Could we just have an option Z that states the guidance notes in this user guide will be followed? This was an answer really to the first question we got about the time bar extension and how well it might stand up in court. I think there's a good point being made here which is if we brought the user guides in as part of the contract, and I think they're there really to advise on how to use it, you know, interpretation, I think it's gone past what the original purpose was. I think we'd be moving in the right direction and as a default set of behaviours you'd be in a much better position. Yeah, and I think the question, Colin's underlying question of the first one is, you know, well why don't we just make the guidance part of the contract? Yeah, and you'd probably be close to where we want to be. I think the only challenge we'd have from a legal point of view is the guidance is guidance, isn't it? It's not black and white rules. I think there would need to be an exercise done to kind of hardwire what aspects were being asked to do, what aspects are maybe optional. But yeah, it's a good thought.

Glenn, I've got one there, have you got any on yours? I think this one's interesting and it's a topic we've certainly covered a few times, it came up the last one with Peter. The point around the requirement for all contractors to pay a subcontractor on the same terms as the client contractor. In some instances, this isn't possible due to long-standing commercial relationships. How do you approach this? Well, first of all, the contract currently doesn't state that all subcontractors have to be back to back. It says the main contract conditions should appear in the subcontract. So in a way, you could write the whole thing yourself. It just has to have the same clauses within the main contract. I think the question is why would you, if you're bringing a subcontract with different terms to that main contract, where would that leave you commercially? Well, it could leave you in trouble, couldn't it? Because there could be gaps. There could be things that mean you're not able to recover down the line what you're being asked to carry out today. I've seen this happen quite a lot. People have different contracts that they've worked out over the years, and that can work and may do and may have done for many years. The problem comes when it doesn't work. And then there's a dispute around those terms. So I think just be careful. There's certainly no rule against it. You don't have to use NEC subcontract. However, the option that's been chosen, particularly the payment mechanism, really does need to align to the main contract. That would be the biggest concern.

Glenn, are there any, oh, actually Colin's putting a good comment in there. It probably works in long standing framework relationships, but I probably wouldn't do it on a one-off. Yes. Okay. You've got a couple of questions in about, Glenn, we've got six minutes. So maybe we could, oh, here's another one that just appeared. I just saw that one. Deleting the contractor's share. Okay, so deleting the contractor's share on option C, for example, essentially turns it into an option E, which is a cost reimbursable. And the contractor just gets their fee and there's no additional contractor's share. And probably that's not going to be a disaster of a clause. It's just whether or not the project manager has been resourced to deal with a cost-based contract. If they haven't, it could spin out of control. And there's a reason for the contractor's share. There's a reason why it exists. It's there to encourage good performance, to keep costs and time down. And to take that away means the value for money is being picked up through a more rigorous governance. So yes, if you're going to remove it, make sure it's being replaced by something that is at least as effective.

Is deleting X18 likely to be cost effective? Well, X18 is the limitation of liability. I think it depends on where you're coming from. If you've got it, it should have been priced from the beginning. If you're now removing it, you're probably opening up the contractor to risk that wasn't priced from the beginning. And that could be very significant. So I think if you're on the contractor side and you've been asked to remove this, then I think it would be very reasonable to ask why, what's the issue here, and to price up any removal or ask for better terms than the current ones, because to unilaterally accept the removal of a limitation of liability sounds pretty serious and significant. I think we have some limitations. As some of you might know, I used to work for Gather before it was Gather. So, but I also work for Infrastructure Scotland and Sellafield and other big blue chip clients. And part of my remit in helping them has been about these limitations. And often they get unlocked by the inclusion of the word wilful within them. So wilful default, misconduct, that sort of thing. So that the contractor is not sleeping easily knowing that they've got a limited liability when they've been completely reckless or wilful with something.

I would, because we've got a minute left, Glenn, let me just talk to this last one because I think it's an interesting one. So the question is, our engineering framework is moving to NEC4 from JCT from 2025. We are in discussion with the local authorities to try and avoid over the top Z clauses. Absolutely. So as David said, having that engagement and discussion pre-tender is exactly right. So if you're writing the procurement documents and you are minded to include these things, then now is the time to discuss them. And of course, the context of the wider project or program or framework could be a factor as well. I think best practice in this sense would be for those proposing to include such clauses to share their thinking as early as possible. And then you've got pre-qualified candidates who can then respond and you can get into a dialogue. So having that dialogue is very important, but try to do it as early as possible and then it's in the open and transparent and everybody can make decisions armed with the right intelligence.

Great. OK, so we're going to wrap up there. Thanks, everybody. That was fun. And we'll see you next time.

.webp)